Puppy Tribulations...in three parts |

Part one - When all is not as it seems...

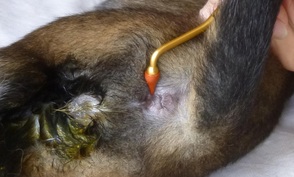

This past summer, we had a lovely and much anticipated litter of nine Leonberger puppies. Their mother, Nubi, (Lionscourt Danubia) was young and fit, having just had her third birthday two days before the birth. They were large puppies, and Nubi had carried 12 originally. We had lost one from a prolonged breech and a second still born arrived 12 hours later. Sad losses, but not uncommon events. A third had a rare congenital developmental problem, called an imperforated anus, which causes the rectum to end in a pouch within the abdomen, rather than continue to the outside. The prevalence of this condition in dogs is not clear, but it is more often seen in puppies than kittens, and is not an uncommon defect in livestock. Apparently one in 5000 human babies also have some degree of abnormality in this area. This defect is the result of a developmental error which prevents the normal deterioration of the anal membrane present in the foetus, leaving a solid plug of tissue between what can appear to be a normal anus and the termination of the large intestines within the tummy. Sometimes the fault is obvious because a large area of normal puppy backside is missing, often including the entire tail, and there is only blank skin where the anus should be. Other times, the outer sphincter does form correctly, but it is like a false door, opening onto a solid wall inside. These are the ones that are easy to miss when, in the middle of an overnight whelping, you quickly do a “top and tail” examination of each new pup for obvious faults such as a cleft pallet. In the pages of the “whelping bible” - the Book of the Bitch - there is a one line mention of this condition, recommending that you check carefully for a fully formed anus because “it is surprising how long a pup can last without an anal opening”. I found out the hard way that this is indeed true.

The reason that they survive at first is that in some cases a fistula or tunnel forms as the body tries to find another route out between the dead-end of the rectum and an alternative passage. In dog puppies, this is rarely successful and abdominal bulging may be the first signs of trouble. In some cases burst abdomens have actually been reported. In bitches it can be quite different, as was the case with ours. A recto-vaginal fistula can and often does form rather swiftly. The problem with this, (apart from the obvious ones), is that due to the exclusive diet of mother’s milk, and the soft faeces that this produces, and due to the fact that a fastidious dam is always keeping her pups backsides’ clean, the pup copes well and shows no early signs of distress. In fact our little Green Ribbon Girl was fat and happy, muscling her way to the head of the queue at the milk bar, at the top of her class for weight gain and sleeping soundly. She had no apparent bulges or other outward signs other than what had appeared to be a brief bout of constipation on her second day, which momma Nubi’s vigorous licking seemed to have sorted out in no time. After that she was fine, and to all intents and purposes was a perfectly normal puppy.

I was sleeping next to the whelping box as I always do for the first few weeks, and little Green Ribbon was latching on- filling up- and rolling off to sleep again with the comforting regularity all breeders want to see in those first days. All that changed on the morning of the 15th day, when suddenly, at 9 am, she started screaming and was clearly in great distress. When I flipped her over, I saw diarrhoea coming out of her vulva. So, straight to the vet she went. Once there I told the vet that I suspected an imperforated anus and he quickly confirmed it. Although she appeared to have a normal bum-hole sphincter formation under her tail, there was in fact nothing behind it but a solid wall of tissue. Because 2 weeks had passed, and because the fistula had likely formed straight away, he thought it likely that the blockage was deep, that there had by now been a rupture, that she was in early-stage peritonitis along with probable urinary tract infection, and that surgical repair would be risky, with a high chance of wound breakdown and a strong possibility of a lifetime’s double incontinence. Meanwhile, the poor pup was in agony. So I made the hard decision to let her go, which is never easy. That evening, I called her future owner and broke the news to her, which is again, never easy.

Like a cleft pallet, this is easy to miss in a newborn pup. But unlike a cleft pallet, it is a problem that can hide for a while, especially in bitch puppies when a fistula forms into the vaginal canal. So I urge all my fellow breeders, check carefully and check often that all is well at both ends when your new pups arrive into the world, and keep doing so for their first few weeks. And if in doubt- check it out. Some imperforated anuses are simple and a little snip is all it takes. Others can have longer blockages, which are much more challenging. Apparently, the sooner an imperforated anus is discovered, the greater the chances that a surgical repair will work. If you want to know more about this condition, here is an academic article detailing surgical repair options for this condition: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1914316/

This past summer, we had a lovely and much anticipated litter of nine Leonberger puppies. Their mother, Nubi, (Lionscourt Danubia) was young and fit, having just had her third birthday two days before the birth. They were large puppies, and Nubi had carried 12 originally. We had lost one from a prolonged breech and a second still born arrived 12 hours later. Sad losses, but not uncommon events. A third had a rare congenital developmental problem, called an imperforated anus, which causes the rectum to end in a pouch within the abdomen, rather than continue to the outside. The prevalence of this condition in dogs is not clear, but it is more often seen in puppies than kittens, and is not an uncommon defect in livestock. Apparently one in 5000 human babies also have some degree of abnormality in this area. This defect is the result of a developmental error which prevents the normal deterioration of the anal membrane present in the foetus, leaving a solid plug of tissue between what can appear to be a normal anus and the termination of the large intestines within the tummy. Sometimes the fault is obvious because a large area of normal puppy backside is missing, often including the entire tail, and there is only blank skin where the anus should be. Other times, the outer sphincter does form correctly, but it is like a false door, opening onto a solid wall inside. These are the ones that are easy to miss when, in the middle of an overnight whelping, you quickly do a “top and tail” examination of each new pup for obvious faults such as a cleft pallet. In the pages of the “whelping bible” - the Book of the Bitch - there is a one line mention of this condition, recommending that you check carefully for a fully formed anus because “it is surprising how long a pup can last without an anal opening”. I found out the hard way that this is indeed true.

The reason that they survive at first is that in some cases a fistula or tunnel forms as the body tries to find another route out between the dead-end of the rectum and an alternative passage. In dog puppies, this is rarely successful and abdominal bulging may be the first signs of trouble. In some cases burst abdomens have actually been reported. In bitches it can be quite different, as was the case with ours. A recto-vaginal fistula can and often does form rather swiftly. The problem with this, (apart from the obvious ones), is that due to the exclusive diet of mother’s milk, and the soft faeces that this produces, and due to the fact that a fastidious dam is always keeping her pups backsides’ clean, the pup copes well and shows no early signs of distress. In fact our little Green Ribbon Girl was fat and happy, muscling her way to the head of the queue at the milk bar, at the top of her class for weight gain and sleeping soundly. She had no apparent bulges or other outward signs other than what had appeared to be a brief bout of constipation on her second day, which momma Nubi’s vigorous licking seemed to have sorted out in no time. After that she was fine, and to all intents and purposes was a perfectly normal puppy.

I was sleeping next to the whelping box as I always do for the first few weeks, and little Green Ribbon was latching on- filling up- and rolling off to sleep again with the comforting regularity all breeders want to see in those first days. All that changed on the morning of the 15th day, when suddenly, at 9 am, she started screaming and was clearly in great distress. When I flipped her over, I saw diarrhoea coming out of her vulva. So, straight to the vet she went. Once there I told the vet that I suspected an imperforated anus and he quickly confirmed it. Although she appeared to have a normal bum-hole sphincter formation under her tail, there was in fact nothing behind it but a solid wall of tissue. Because 2 weeks had passed, and because the fistula had likely formed straight away, he thought it likely that the blockage was deep, that there had by now been a rupture, that she was in early-stage peritonitis along with probable urinary tract infection, and that surgical repair would be risky, with a high chance of wound breakdown and a strong possibility of a lifetime’s double incontinence. Meanwhile, the poor pup was in agony. So I made the hard decision to let her go, which is never easy. That evening, I called her future owner and broke the news to her, which is again, never easy.

Like a cleft pallet, this is easy to miss in a newborn pup. But unlike a cleft pallet, it is a problem that can hide for a while, especially in bitch puppies when a fistula forms into the vaginal canal. So I urge all my fellow breeders, check carefully and check often that all is well at both ends when your new pups arrive into the world, and keep doing so for their first few weeks. And if in doubt- check it out. Some imperforated anuses are simple and a little snip is all it takes. Others can have longer blockages, which are much more challenging. Apparently, the sooner an imperforated anus is discovered, the greater the chances that a surgical repair will work. If you want to know more about this condition, here is an academic article detailing surgical repair options for this condition: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1914316/